Heat-sensing Fire Detectors

Heat-sensing fire detectors shall be installed in all areas where assessed as per standards or by the authority having jurisdiction. The relationship between heat and temperature must be understood if heat-sensing detectors are to be applied properly.Heat is energy and is quantified in terms of an amount, usually British thermal units (Btu) or Joules (J). Temperature is a measure of the quantity of heat in a given mass of material and is measured as an intensity, quantified in terms of degrees Farenheit or Celsius.

The majority of the heat flowing into a heat detector is from the hot gases that comprise the ceiling jet. This is called convective heat transfer. A much smaller portion of the heat absorbed by a heat detector is transferred by radiation, a process called radiant heat transfer.

Heat detectors operate on one or more of three different principles. These operating principles are categorized as fixed temperature, rate compensation, and rate-of-rise. Each principle has its performance advantages and can be used in either a spot-type device or a line-type device.

Most heat detectors are devices that change in some way when the temperature at the detector achieves a particular level, or a set point, as in a fixed-temperature type. Other detectors respond to the rate of temperature change, as in a rate-of-rise heat detector.

Heat detectors are available in two general types: spot-type, which are devices that occupy a specific spot or point; and line-type, which are linear devices that extend over a distance, sensing temperature along their entire length.

A number of different technologies can be used to detect the heat from a fire, including

the following:

- Expanding bimetallic components

- Eutectic solders

- Eutectic salts

- Melting insulators

- Thermistors

- Temperature-sensitive semiconductors

- Expanding air volume

- Expanding liquid volume

- Temperature-sensitive resistors

- Thermopiles

The designer must be careful not to confuse the terms, type and principle with technology, which

is the method used to achieve heat detection.

General

Before installation of Fire detectors some performance related objectives should be describe the purpose of the detector, placement and the intended response of the fire alarm control unit to the detector activation.The performance objective of a fire detection system is usually expressed in terms of time and the size fire the system is intended to detect, measured in kilowatts (kW) or British thermal units per second (Btu/sec). Typically, the fire alarm system designer does not establish this criterion. It is usually obtained from the design documentation prepared by the designer responsible for the strategy of the structure as a whole. Where a prescriptive design is being provided, this requirement is fulfilled by stating in the design documentation that the design conforms to the prescriptive provisions.

A fire protection strategy is developed to achieve those goals. General performance objectives are developed for the facility. These general objectives give rise to specific performance objectives for each fire protection system being employed in the facility. Consequently, the performance objectives and criteria for the fire alarm system are part of a much larger strategy that often relies on other fire protection features, working in concert with the fire alarm system to attain the overall fire protection goals for the facility.

In the performance-based design environment, the designer uses computational models to demonstrate that the spacing used for automatic fire detectors connected to the fire alarm system will achieve the objectives established by the system, by showing that the system meets the performance criteria established for the system in the design documentation.

Consequently, it is imperative that the design objectives and performance criteria to which the system has been designed are clearly stated in the system documentation.

Temperature Classification

The performance of a heat detector depends on two parameters: its temperature classification and its time-dependent thermal response characteristics. Traditionally, the temperature classification has been the principal parameter used in selecting the proper detector for a given site.An additional objective is to select a detector that will be stable in the environment in which it will be installed.

Color Coding

Heat-sensing fire detectors of the fixed-temperature or rate-compensated, spot-type shall be classified as to the temperature of operation and marked with a color code in accordance with Table given belowException: Heat-sensing fire detectors where the alarm threshold is field adjustable and that are marked with the temperature range.

Spot-type heat detectors are currently the most widely used type of heat detector for general purpose use.

Not all heat detector manufacturers use this color code. Some manufacturers simply provide a label on the side or bottom of the detector. When the unified color coding of heat detectors is used, it facilitates inspections, making it possible to identify the temperature rating of a ceiling-mounted heat detector while standing on the floor. The color code for heat detectors is very similar to that used for sprinkler heads, as per NFPA 13.

Manufacturers also provide this information in their data sheets for each type of heat detector. The commercial availability of solid state thermal sensors and analog/ addressable fire alarm system control units has made possible the development of analog/addressable heat detectors. These detectors permit the designer to adjust the alarm threshold temperature at the fire alarm control unit and select a unique threshold temperature based on an analysis of the compartment and the fire hazard. A color code would be meaningless for this technology and consequently is waived. Clearly, when analog/addressable technology is used, an alternative means for facilitating inspection should be in place.

Integral Heat Sensors

A heat-sensing fire detector integrally mounted on a smoke detector shall be listed or approved for not less than 15 m (50 ft) spacing.The linear space rating is the maximum allowable distance between heat detectors. The linear space rating is also a measure of the heat detector response time to a standard test fire where tested at the same distance. The higher the rating, the faster the response time. This Code recognizes only those heat detectors with ratings of 15 m (50 ft) or more.

The customary spacing of smoke detectors is 9.1 m (30 ft), and because smoke detectors are primarily considered to be fulfilling an early warning role, the heat detector, if deemed a necessary addition to the smoke detector, should be sufficiently sensitive to provide a response before the fire has grown to an excessive size. In order for the heat sensor portion of the detector to fulfill this expectation, it must have a 15-m (50-ft) spacing factor.

Marking

Heat-sensing fire detectors shall be marked with their listed operating temperature.The marking of the heat detector should be with both the temperature rating and its thermal response coefficient (TRC).

The response of a heat detector is determined by two factors: its temperature rating and the speed with which it can absorb heat from the surrounding air. The temperature rating is easily measured and the requirement for marking the detector with the temperature set point has existed for many years. The second factor is TRC. The research needed to develop a method for quantifying TRC is under way. Until a verified value for the TRC for each make and model heat detector is available, our ability to predict when that heat detector will operate in relation to the development of a fire is limited and imprecise. Consequently, the lack of a TRC limits the use of such heat detectors in performance-based designs.

Some researchers have used the response time index (RTI) as a measure of the thermal response of a heat detector [Alpert, 1972; Evans and Stroup, 1986]. RTI is determined by means of a plunge test that was originally designed to test the response characteristics of sprinkler heads. The plunge test uses a simulated ceiling jet velocity of 1.5 m/sec (5.0 ft/sec). Other researchers have raised questions regarding this measurement, because heat flow from the ceiling jet to a detector is proportional to ceiling jet velocity [Brozovski, 1989;Heskestad and Delichatsios, 1989]. Because the spacing between heat detectors is often much greater than the spacing between sprinkler heads, the jet velocities normally encountered at the heat detectors are often an order of magnitude smaller than those encountered at the sprinklers. Therefore, using RTI as a measure of heat detector sensitivity presumes a much larger fire and could introduce important inaccuracies. Consequently, a TRC for heat detectors

derived from a test specifically designed for the purpose is necessary.

The adoption of the concept of a TRC presumes the development of a test method to determine the coefficient. When such a test becomes available, it will become part of the listing evaluation for heat detectors. Because the test is still in development, a requirement for marking the detector with its TRC was removed from this edition.

Location

The location stipulated takes maximum benefit of the ceiling jet produced by a fire. Because the occurrence of a ceiling jet causes the hot combustion product gases to flow outward and away from the fire plume center line, a ceiling location provides for the maximum flow across the detector and the maximum speed of response to a growing fire.Spot-type heat-sensing fire detectors shall be located on the ceiling not less than 100 mm (4 in.) from the sidewall or on the sidewalls between 100 mm and 300 mm (4 in. and 12 in.) from the ceiling.

In compartments equipped with heat detection, spot-type heat detectors must be located on the ceiling at a distance 100 mm (4 in.) or more from a vertical side wall, or on the side wall between 100 mm (4 in.) and 300 mm (12 in.) from the ceiling, measured to the top of the detector.

The ceiling location derives the maximum benefit from the upward flow of the fire plume and the flow of the ceiling jet beneath the ceiling plane. The best currently available research data support the existence of a dead air space where the walls meet the ceiling in a typical room. This dead air space extending 100 mm (4 in.) in from the wall and 100 mm (4 in.) down from the ceiling. Consequently, the Code excludes detectors from those areas. As the ceiling jet approaches the wall, its velocity declines. Lower ceiling jet velocities result in slower heat transfer to the detector and, therefore, a retarded response. The prudent designer will keep detectors further from the wall than the 100 mm (4 in.) minimum distance.

In the case of solid joist construction, detectors shall be mounted at the bottom of the joists.

The definition of the term joist must be inferred from the definition of solid joist construction, found under Ceiling Surfaces in subsection 3.3.24. Joists are solid projections, whether structural or not, extending downward from the ceiling, that are more than 100 mm (4 in.) in depth and are spaced on 0.9 m (3.0 ft) centers or less. The commonly encountered 50 mm , 250 mm (2 in, 10 in.) rafter installed on 400 mm (16 in.) centers supporting a roof deck is typical of solid joist construction.

The structural component commonly called abar-joistis actually an open web beam. If the upper web member of an open web beam is less than 100 mm (4 in.) deep, the beam is ignored. If it is more than 100 mm (4 in.) deep, it is called either a joist or a beam, depending on the center-to-center spacing.

The narrow spacing between joists [usually approximately 380 mm (15 in.) for joists on 400 mm (16 in.) centers] creates air pockets. These air pockets have two effects on the flow of the ceiling jet. First, the air pockets tend to slow the ceiling jet; second, the air pockets force the ceiling jet to flow across the bottoms of the joists. Because the dominant flow regime of the ceiling jet will be along the bottoms of the joists, requires that heat detectors be placed on the bottoms of joists rather than up in the pockets between them. This placement puts the detectors in the region of maximum ceiling jet flow.

In the case of beam construction where beams are less than 300 mm (12 in.) in depth and less than 2.4 m (8 ft) on center, detectors shall be permitted to be installed on the bottom of beams. A definition of beam must be inferred from the definition of beam construction found under Ceiling Surfaces. Beams are effectively defined as solid projections, whether structural or not, extending downward from the ceiling, that are more than 100 mm (4 in.) in depth and are spaced on centers of more than 0.9 m (3.0 ft). In the context of the Code, the principal distinction between a joist and a beam is the center-to-center spacing.

The installation of heat detectors on the beam bottoms only when the beams are less than 300 mm (12 in.) deep, and only when the beams are on centers of less than 2.4 m (8 ft). If the beams are more than 300 mm (12 in.) deep or if they are spaced more than 2.4 m (8 ft) apart, the detectors must be placed on the ceiling surface between the beams.

Finally, the only permitted location for spot-type heat detectors is at or in close proximity to the ceiling plane. There is no research to provide guidance for detector placement in areas without ceilings. By inference, if there is no ceiling in the hazard area on which to locate heat detectors, then heat detection cannot be installed in compliance with the prescriptive requirements of the Code

Line-type heat detectors shall be located on the ceiling or on the sidewalls not more than 500 mm (20 in.) from the ceiling.

In the case of solid joist construction, detectors shall be mounted at the bottom of the joists.

In the case of beam construction where beams are less than 300 mm (12 in.)

In depth and less than 2.4 m (8 ft) on center, detectors shall be permitted to be installed on the

bottom of beams.

Where a line-type detector is used in an application other than open area protection, the manufacturer’s installation instructions shall be followed.

Temperature

Detectors having fixed-temperature or rate-compensated elements shall be selected in accordance with table given above for the maximum expected ambient ceiling temperature. The temperature rating of the detector shall be at least 11 C (20 F) above the maximum expected temperature at the ceiling.Detectors should be selected to minimize this temperature difference in order to minimize response time. However, a heat detector with a temperature rating that is somewhat in excess of the highest normally expected ambient temperature is specified in order to avoid the possibility of premature operation of the heat detector to non-fire conditions.

Spacing

In addition to the special requirements for heat detectors that are installed on ceilings with exposed joists, reduced spacing also could be required due to other structural characteristics of the protected area, such as possible drafts or other conditions that could affect detector operation.Smooth Ceiling Spacing

The number of detectors required is a function of the spacing factor,S, of the chosen detector.The spacing is established through a series of fire tests conducted in the listing evaluation by the qualified testing laboratory listing the detector. The spacing is an approximation of the relative sensitivity of the detector.

The spacing derived from the fire tests relates heat detectors to the response of a specially chosen 71.1 C (160 F) automatic sprinkler head. The fire test room has a ceiling height of 4.8 m (15 ft, 9 in.) above the floor and has no airflow. The test fire is situated at the center of a square array of the test sprinkler heads, installed on 3 m 3 m (10 ft 10 ft) centers.

This places the center line of the test fire 2.2 m (7.07 ft) from the test sprinklers.

Heat detectors are mounted in a square array that is centered about the test fire with increased spacings. The fire is located approximately 0.9 m (3.0 ft) above the floor and consists of a number of pans of an ethanol/methanol mixture yielding an output of approximately 1200 kW (1138 Btu/sec). The height of the test fire and the fire area are adjusted to produce a time versus temperature curve at the test sprinklers that falls within the envelope established for the test and causes the activation of the test sprinkler at 2 minutes 10 seconds. The greatest detector spacing that produces an alarm signal before a test sprinkler actuates is the listed spacing for the heat detector.

Heat detector performance is defined relative to the distance at which it could detect the same fire that fused the test sprinkler head in 2 minutes 10 seconds. For example, a heat detector installed on a 15.2 m 15.2 m (50 ft 50 ft) array receives a 15.2 m (50 ft) listed spacing if it responds to the test fire just before the test sprinkler head operates.

It is important to keep in mind that the listed spacing for a heat detector is a lumped parameter, a number of variables, including fire size, fire growth rate, ambient temperature, ceiling height, and TRC are lumped into a single parameter called listed spacing. The listed spacing is sufficiently accurate to compare two heat detectors to each other, but it cannot be used to predict when a given detector will respond, except in the context of the fire test. Outside the context of the listing test, the listed spacing is only a relative indication of the detector thermal response.

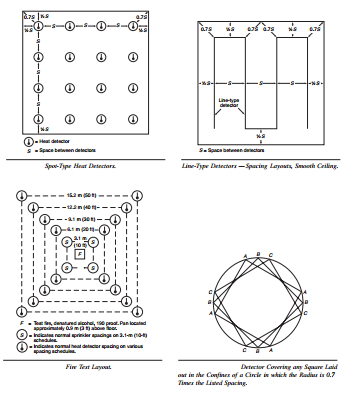

Maximum linear spacing on smooth ceilings for spot-type heat detectors are determined by full-scale fire tests. These tests assume that the detectors are to be installed in a pattern of one or more squares, each side of which equals the maximum spacing as determined in the test. The detector to be tested is placed at a corner of the square so that it is positioned at the farthest possible distance from the fire while remaining within the square. Thus, the distance from the detector to the fire is always the test spacing multiplied by 0.7 and can be calculated.

Once the correct maximum test distance has been determined, it is valid to interchange the positions of the fire and the detector. The detector is now in the middle of the square, and the listing specifies that the detector is adequate to detect a fire that occurs anywhere within that square—even out to the farthest corner.

In laying out detector installations, designers work in terms of rectangles, as building areas are generally rectangular in shape. The pattern of heat spread from a fire source, however, is not rectangular in shape. On a smooth ceiling, heat spreads out in all directions in an ever-expanding circle. Thus, the coverage of a detector is not, in fact, a square, but rather a circle whose radius is the linear spacing multiplied by 0.7.

With the detector at the center, by rotating the square, an infinite number of squares can be laid out, the corners of which create the plot of a circle whose radius is 0.7 times the listed spacing. The detector will cover any of these squares and, consequently, any point within the confines of the circle.

So far this explanation has considered squares and circles. In practical applications, very few areas turn out to be exactly square, and circular areas are extremely rare. Designers deal generally with rectangles of odd dimensions and corners of rooms or areas formed by wall intercepts, where spacing to one wall is less than one-half the listed spacing. To simplify the rest of this explanation, the use of a detector with a listed spacing of 9.1 m 9.1 m (30 ft 30 ft) should be considered. The principles derived are equally applicable to other types.

One of the following requirements shall apply:

- The distance between detectors shall not exceed their listed spacing, and there shall be detectors within a distance of one-half the listed spacing, measured at a right angle, from all walls or partitions extending to within 460 mm (18 in.) of the ceiling.

- All points on the ceiling shall have a detector within a distance equal to 0.7 times the listed spacing (0.7S).

For irregularly shaped areas, the spacing between detectors shall be permitted to be greater than the listed spacing, provided the maximum spacing from a detector to the farthest point of a sidewall or corner within its zone of protection is not greater than 0.7 times the listed spacing.